As a 21-year-old woman raised in America, I often felt vindicated. Once I entered the progressive world of college, I preached the idea that life was unfair for women, especially when compared to our counterparts – both the bane and the desire of my existence – men.

I was unhappy about my period. I was unhappy about misogynistic men (or as I would have referred to them: boys) at my university. I was unhappy that my mom wouldn’t let me wear a bikini around my dad. But at the same time, I relished in this dynamic of “who has it worse?”

I felt best about myself when gaining attention from men because I thought I deserved it. (Us women, after all, we put up with for men? The least they can do is please us, right?) I was what my friends called a relationship junkie; I bounced between relationships because I really did love love… or at least the beginning part of it when everything is new. I relished in dating men who would open up doors for me, and the best were the ones who would shower me with praise.

Women’s treatment in the world didn’t feel perfect though; I spent a great amount of energy fixating on what was unfair about a woman in my position. It feels disappointing how rarely I did celebrate the privileges I had as a young, American woman, but I am glad to be reflecting upon the moment when these privileges revealed themselves to me. And I am happy about the way that it happened. I hope that, without this experience, I would have come to the same realization, but I can’t say.

I know that when I was 21 years old, I was wrapped up in myself in a way that doesn’t sustain a healthy life. It wasn’t that I was too selfish to look at my privileges head-on; rather, I feel I had been blind to experiences that allowed me to see what life is like for other women. Maybe these experiences and life lessons had always been waiting around me and I just hadn’t taken the bait. I hope that, for anyone reading this who was like me, maybe this story of mine can be your bait.

Junior year, I studied abroad in Tanzania. I worked as a waitress to save money. My heart just swells when I think back to how excited I was. I was about to experience a month of my life that stands out among all other memories like an anomaly, like a dream; it feels warm and hazy when compared to the hues of all my other memories. I lived in a rural village part of the coast, hours from the nearest electricity. We swam each day and I had class at night, the ocean salt grazing my face as I wrote by lantern in the sand.

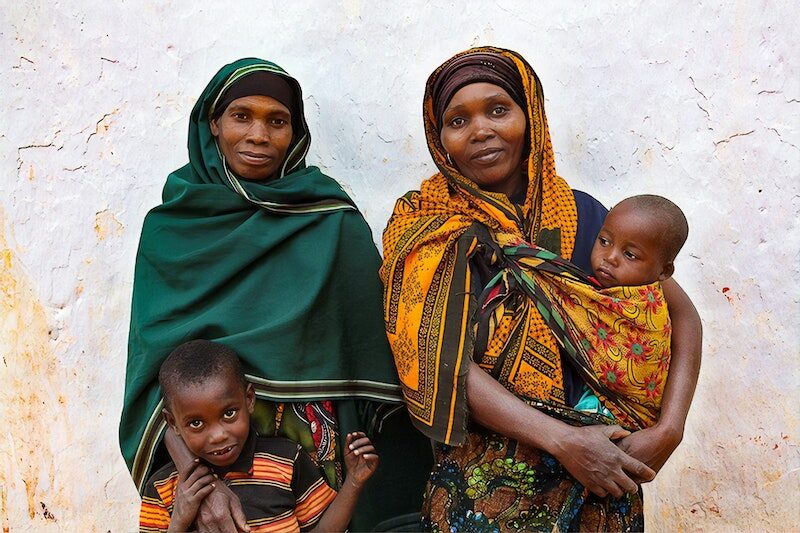

A small group of us sailed each morning to a secondary school across the bay where I spent my afternoons teaching years seven and eight English with a local teacher counterpart, Muhenga (a word that translates to “wise man”). There were female teachers at Zingibari Secondary, as well: the terrifying Madame Hasna, whose skin was near as aged and black as the hijab and robe she wore daily (She washed my feet once when I entered her home. She had to lend me a skirt because my pants had torn from the saltwater on the journey there), and the delightfully loud Fatima with a smile that took up her entire face. She had the whitest teeth you’ve ever seen. There were other women in the village, too; one woman brought us bread and had tea with us every morning. Her daughter, who seemed around my age, was both cognitively and physically disabled; I remember she reminded me of my cousin with cerebral palsy. She always took care of her little siblings when her mom had tea with us. They adored her.

Life was different here. For starters, the teachers had wonderfully long breaks during the school day when the students were required to do chores around the schoolyard. We would drink tea and eat beignets, laughing at the funny ways we said each other’s words. One morning tea found just the ladies together, and as women tend to do, we began to gossip; the women asked me if any local men had shown interest in me.

Men here were much different than the men in America, and I had liked to think of myself as an expert on the latter. In Tanzania, men were romantic and grand in their gestures, promising to build you a home in Arusha that overlooks the ocean or to travel back to America to spend every waking moment working so they can spoil you adequately. I enjoyed flirting with them, seeing how much they would offer for a dowry, how much I was worth in this man’s eye. (It makes my stomach turn to think back to how I spoke to them as I negotiated how many cows they’d be willing to give for me.)

Part of my flippancy was clearly due to immaturity and a lack of understanding of the world; however, there were certain aspects of the culture I was taking advantage of while “harmlessly” flirting. Men, for example, could legally have four wives; women, however, could only maintain one husband, and adultery committed by a woman was met with worse social repercussions than by a man. Married couples were arranged through dowries and contracts were drawn up delineating when the wife could leave the home and how many children she was to bear. Men spent alternating weekends with their alternating families with about five or six children to a family on average. Muhenga was the one who explained these cultural norms to me, but it didn’t hit me until I spoke with the women.

The ladies asked about my love life back home and asked me if I had a husband. I told them, “No, but I’m dating someone right now.” I had just begun to date a new guy, and things were as serious as they could be when you were twenty-one years old. They asked me, looking surprised: “Dating? How many boys do you date?” I explained to them I had dated numerous boys especially since I had been to college; “If they don’t suit me, I kick ’em to the curb,” I told them jokingly. I laughed about how flippant it was to sleep with men in college back home. I looked around to see the women looking back at me in the eyes with solemnity – what emotion were they showing? Was it disgust? No, I realized: it was fear. Fatima asked so kindly but cautiously: “And with each boy you date… you have sex with them? All of them?”

I told the ladies that yes, that’s usually how it goes, and the jaws of my female coworkers dropped – seriously, and they looked at one another. One said, “What do they think of you?” and another asked, “And… you don’t have… AIDS?” My smile immediately faded from my face. I felt myself sitting there, looking at these women who were genuinely worried about me. It was not like a switch was flipped, but it was the first time that my feminine privilege hit me in the face like that. Humiliated, I realized I was discussing such a sensitively viewed topic in their culture – female sexuality – in such a light-hearted way, almost disrespectful by the way I was laughing. (I am so thankful for the relationships I had with these women, and the understanding they maintained for my cultural blindness. They were so gentle and kind toward me, and it feels even more apparent when I look back at the attitude I emanated.)

We continued speaking for a long time about how they had lost a student the previous semester from AIDS (her mother had passed it to her genetically), and how they all had husbands they were essentially given to. My friend with the huge smile talked about how she still needed to have two more children per her marriage contract, but how it was tough to time it when he was gone three weeks out of the month with his other families. Madame Hasna explained how she had to ask each time she wanted to leave the house unless it was to retrieve food or go to work. If she wanted an afternoon to herself to go to the city shopping, for example, she would have to ask him. It made me sad to picture this strong woman the children (and sometimes, me) feared, cautiously approaching her husband to ask permission to leave. (This would only be, of course, if women in this village were allowed out alone like that.)

There were aspects of my life that were considered “normal” back at my American university, but these women allowed me to see the privilege in my normal. These women could not explore their sexualities or date different men until they found one that “suited them.” I realized how lucky I was to go shopping when I wanted to, to have a say in how many children I wanted. I could exist as a woman exploring her sexuality within the safety and comforts of my culture. I realized that by the “harmless” flirting I had done with the local men, I was taunting my fellow females with my privilege. What a wonderful position to be in – from the outside looking in. I had never seen it that way, not like this.

I suddenly became hyper-aware of more that I had taken for granted: I always grabbed too many paper towels after using a public restroom, and I never questioned where my water came from. I started making an effort to recognize things like this. I stopped dating around for good – really. I ended up marrying the guy I had told the ladies about. And I sometimes wonder, did these women have anything to do with the way, I looked at my relationship with men, at my relationship with myself as a woman?

Absolutely, yes.