“I want to die.”

It was hard to hear when my mother first said the words to me over the phone, but I understood why she felt that way.

Besides robbing her of memory, that thief dementia had stolen my mom’s independence, dignity and ability to have an adult conversation. She repeated herself incessantly and often had trouble spitting out a coherent thought.

“Oh, never mind,” she’d say when she couldn’t get the words out.

I could tell she was confused, frightened and depressed at the turn her life had taken. I tried to imagine what it would be like to wake up in assisted living every morning and not remember where I was or why I was there. The thought terrified me.

“I just want it to be over,” she said, in a rare moment of clarity.

She hadn’t been so definite about anything in five years or more. At first, I didn’t know what to say, but a month later, when my mom repeated her desire to die, I’d had time to think about my response.

“It’s okay, Mom. I completely understand.”

My mother had always been a caregiver—a nurse, a wife and mother, a hospice director, chaplain and Episcopal priest. She was an early disciple of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, whose book On Death and Dying identified those now iconic five stages of grief: anger, denial, bargaining, depression and acceptance. For more than 30 years, my mom sat at the bedsides of countless patients and parishioners as they took their last breaths, and she ran grief groups for the bereaved.

In her work, she supported terminally ill people’s desire to die at home comfortably with their physical and spiritual needs met, and she trained dozens of hospice volunteers over the years to attend to dying patients and their families.

It was through my mother’s own example that I was able to cobble words together giving her permission to die.

“We’d sure miss you, Mom, but I want you to know it’s okay if you want to go.”

Despite dementia, high blood pressure and a lingering shoulder disability from the dreadful fall that started my mom’s downward spiral nearly eight years earlier, she wasn’t actually dying when she began to wish herself dead. She took a lot of medicine to control the high blood pressure, but there was no imminent condition threatening to take her anytime soon. Since she was willing her demise, I prayed she’d simply go to bed one night and not wake up in the morning—a peaceful, uneventful transition, as opposed to a death that was drawn out and traumatic.

My mother’s dementia was caused by Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, a condition with symptoms similar to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Don’t let the name fool you. There’s nothing normal about it. In fact, it’s devastating. It turned this fiercely independent woman who once confidently delivered Sunday sermons into an entirely different person, one who was needy, insecure and uncommunicative.

Besides memory loss and word hunger, the condition is also marked by an unsteady gait and urinary incontinence. The condition required surgery to place a shunt into her brain to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid into the peritoneal cavity of the abdomen, where it would be absorbed. For some people, the procedure leads to improvement, but in my mom’s case, she only got worse.

“Don’t fall!” the neurosurgeon admonished at the end of every appointment.

“If you fall, it’s over.”

He told us that even a minor head injury could cause a fatal brain bleed.

My mom had fallen several times—once after wandering away from her senior living facility. I constantly worried that her death would come as the result of a traumatic brain injury, that she’d bleed out alone on a sidewalk or the floor of her tiny apartment waiting for paramedics instead of surrounded by family, love, and the same hospice care she’d given to so many over the years.

“It was a beautiful death,” my mom said after my father died.

Indeed his passing was calm, peaceful and spiritual. He began receiving hospice care after the doctors told us there was nothing they could do to repair the faulty valve in his heart. He’d already had a couple of open heart surgeries and had too much scarring in his chest from the radiation he’d endured while battling Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Dad was a bad surgical risk and, at age 78, gracefully accepted that his days were numbered.

My mother and I were with him when he died at home. Friends from church had stopped by earlier to pray, and we continued the vigil as his breathing became slow and irregular, assuring my dad of our love and whispering to him that it was all right to go. From my chair next to the bed, I saw his carotid artery pulse for the last time. His mouth was open, his eyes were closed, and his fragile skin was translucent.

I was shocked by the absolute realization that, whatever you call it—spirit or soul or life force—his essence was gone. I no longer saw my father, but rather the shell that had contained him.

Although it didn’t lessen the reality of grief, those many months on hospice helped us prepare for my father’s eventual death. My mother’s end came suddenly. She was in the hospital hooked up to monitors, IVs, a catheter. Seemingly overnight she was in kidney failure, and her heart was going haywire.

When I flew in from the West Coast, I found my mother more lucid than I’d seen her in years. Throughout the day, she’d repeated two things to everyone who entered her room in the Cardiac ICU: “My daughter’s coming!” and “Tomorrow’s my birthday!” That she was aware of and remembered these events were stunning in light of her severe short- and long-term memory loss.

I told my mom about my recent trip to Alaska and read aloud from her prayer book while she dozed. When I left for the night, she told me she loved me and would see me the next day.

They were the last words I ever heard my mother speak.

After I had left, medical staff had to shock her heart back into normal rhythm several times overnight, and by morning her organs were shutting down. It was time to stop. No more heart medication. No more procedures. Just love and comfort. She received medicine to prevent air hunger, panic, and pain. Even in her sleep she occasionally became agitated, grabbing at her blankets and twitching her legs—a sign she needed Ativan, which quickly helped her relax.

My brother and his family, and my daughter and I, spent my mother’s 84th birthday at her side.

A nurse told us the hearing is the last sense to go, so despite her deep slumber, we played a recording of her beloved Handel’s Messiah and whispered to her that it was okay to go, that Daddy was waiting, that we loved her.

We rubbed her hands and feet, stroked her hair, and prayed with various clergy colleagues who stopped in throughout the day. And, of course, we sang “Happy Birthday.”

We didn’t label it at the time, but our family essentially put together our own ad hoc hospice during those last hours of my mother’s life. She died 15 minutes past her last birthday with dignity, without pain and surrounded by love. It was what she’d always modeled for us in her life’s calling in hospice work and pastoral ministry.

It was the best birthday present we ever gave her.

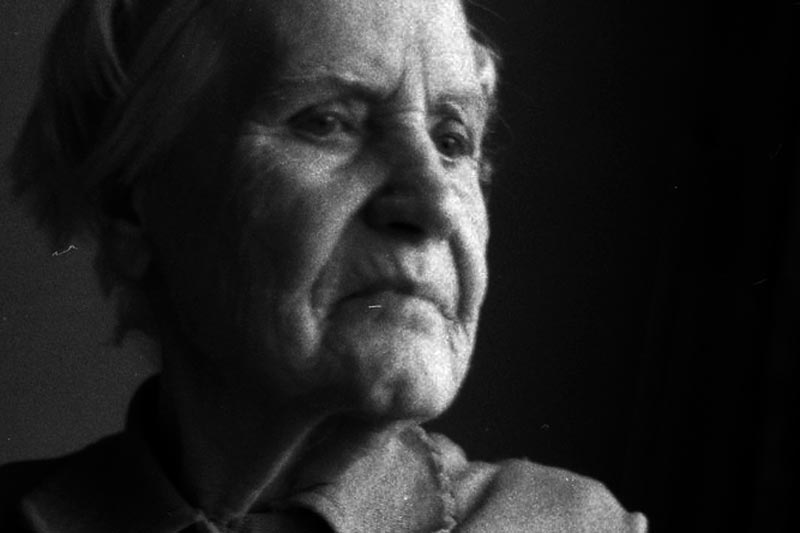

Photo Credit: Ondřej Šálek Flickr via Compfight cc

Hi, Bryan. Thanks for reading the writing. So sorry about your mom. It is really tough. Be good to yourself.

You’re very welcome, Carol. Yes, dementia really stinks!

Beautiful, Mary.

Gawd, I hate dementia. It hurts so much. Thank you for your words.

Hi, Bryan. Thanks for reading the writing. So sorry about your mom. It is really tough. Be good to yourself.

Oh, Dori, thank you. That means the world to me. Your mother is most fortunate for her health and for you to look after her. I hope the two of you have lots more time together. XO

Oh, Kitt. I am so very sorry to hear about your parents and their health issues. Can be such a surreal time. Thank you for sharing that. I hope, too, that their eventual deaths are filled with peace and that you can be, too. Take care of you.

Mary, thank you for writing this piece. My father has alcohol-related dementia. My mother was my father’s caregiver until she had a stroke. Since that time, they have both struggled with dementia. My mother – former college debate team captain who used to spend her days solving crossword puzzles and playing Words with Friends with me and my sister – can no longer speak, read, or write. I pray that their eventual deaths are peaceful.

As difficult as this was to read, Mary, it was actually helpful and hopeful to me. I caregive for my 86-year old mother and although she is healthy now, I dread the day this will happen for her.. Thank you for your honesty, it made reality a little bit easier for me to accept. What a wonderful daughter you are…..D.

Brought tears to my eyes. My mother had Alzheimer’s too.